J. Michael Straczynski's Before Watchmen: Nite Owl/Dr. Manhattan collection (which also includes the two-part Moloch story) is not the best of the Before Watchmen collections overall (Darwyn Cooke's Minutemen/Silk Spectre still takes that prize), but Straczynski's Nite Owl, specifically, may be the best of the Before Watchmen titles.

The Before Watchmen stories have played fast and loose with Watchmen lore by questioning the veracity of Watchmen's main source of back story, the first Nite Owl Hollis Mason's book Under the Hood. Straczynski's Nite Owl takes this a step further, telling a story that seems ridiculously incongruent with the Watchmen story, but then in the end proves itself to be remarkably valid -- a story that, with a second look at Watchmen, seems to have been there all along.

If the purpose of Before Watchmen is to expand one's understanding of Watchmen proper, Nite Owl succeeds, taking a throwaway line and building a universe out of it.

[Review contains spoilers]

As with many of the Before Watchmen stories, labeling Straczynski's tales "Nite Owl" and "Dr. Manhattan" -- even to call the Moloch story "Moloch" -- is something of a misnomer. Nite Owl is Mason and second Nite Owl Dan Dreiberg's story, but it's also Rorschach's; Dr. Manhattan and Moloch star their titular characters, but each strongly gives way to Ozymandias in the end. In fact, if one wanted to project a certain narrative purpose to the collecting of Before Watchmen (that probably isn't there), you could see the first two volumes, Minutemen/Silk Spectre and Brian Azzarello's Rorschach/Comedian books as each having a strong thread of Comedian's journey in them, and Nite Owl/Dr. Manhattan and Ozymandias/Crimson Corsair spotlighting Ozymandias; in this way the Watchmen world, too, passed from the tumultuous age of the Comedian to the faux utopia of Ozymandias.

Nite Owl is mainly Dreiberg and Rorschach's story -- how the two became the crimefighting team we never quite saw in Watchmen, and how that partnership ultimately failed. It is a woman who comes between them, but what Dreiberg's relationship with the Twilight Lady reveals is Dreiberg's budding open-mindedness and Rorschach's budding single-minded determination -- the two are each growing into themselves, but in two different directions. Rorschach's misguided efforts to keep his friend, to reduce it to its simplest terms, is almost sweet -- at one point Straczynski suggests Rorschach somehow manipulates events so that early on Dr. Manhattan is paired with Silk Spectre instead of Dreiberg (though in the Manhattan story Straczynski alternatively suggests Manhattan is the culprit).

For someone less familiar with Watchmen's minutiae, however, the Twilight Lady story seems initially unbelievable. Dreiberg had a weeks-long affair, even revealed his identity, to another crimefighter, she ultimately broke his heart, and she's never once mentioned in Watchmen proper? It seemed Straczynski imagined a step too far. But at the end Straczynski reminds us of a single throwaway line in which Dreiberg pretends to Silk Spectre to have never met "Dusk Woman" (though later dreams about her) and it becomes clear -- crystal clear, like how could we have never seen it before? -- that Dreiberg was lying in that moment. Straczynski's Nite Owl fits -- really, really fits -- and it is a story that unquestionably changes a moment of Watchmen such that I'll never read it the same way again.

Taking for granted, again, that Mason's Under the Hood isn't gospel, Straczynski modifies how Mason and Dreiberg met, beginning the story with what seems like a mundane Batman and Robin analogue. Straczynski, though, ends up in fact offering a new perspective on the Batman/Robin relationship; whereas Bruce Wayne took in Dick Grayson as a partner to continue his war on crime, Mason trains Dreiberg specifically so that Mason might retire, an attitude that helps distinguish the Nite Owls against the more familiar DC Comics heroes.

Dr. Manhattan is a more off-the-cuff story, more a character picture a la Azzarello's Rorschach and Comedian than Nite Owl or Cooke's more weighty adventures. Still, Straczynski plays with time travel and physics well here, ultimately suggesting that the cause of the accident that turned Jon Osterman into Dr. Manhattan was ... Dr. Manhattan himself. There's good parallels between Manhattan and Ozymandias's ultimate Watchmen plan when Manhattan begins destroying alternate timelines (and, one imagines, all the denizens within) in order to preserve his own.

But the real meat of the Manhattan story is in the final pages of the last issue, in which Manhattan recruits Ozymandias to help him see the truth of reality and his existence, which Manhattan himself can't see. Here, the pages themselves turn upside down, as Ozymandias makes Manhattan an unwitting accomplice in Ozymandias's plan to destroy New York to bring about world peace. There's a significant amount happening here: artist Adam Hughes doing well, Ozymandias's evil on display and really detailed for the first time, and even the hint that maybe all of this -- Ozymandias's plan, world peace -- is just one of a number of potential timelines, that maybe it's all in Manhattan's head and that the "true" events of Watchmen unfolded some other way entirely.

The two-part Moloch story can't help but be read, especially as collected, through the lens of the end of the Manhattan story. The first issue, which goes on maybe a bit too long, profiles Watchmen "villain" Moloch's young life; the second issue is really Ozymandias's, not Moloch's, as Moloch too becomes a pawn in Ozymandias's plan, one corpse among many left behind. Art here is by noir artist Eduardo Risso, and it gives the story a real sense of menace. In Watchmen, I believe we're supposed to see Ozymandias as so crazy he might be sane, that Ozymandias might actually be right, but the Moloch story posits Ozymandias as a villain through and through.

Again, J. Michael Straczynski's Nite Owl/Dr. Manhattan is not the strongest of the Before Watchmen collections, but only because the Dr. Manhattan and Moloch stories (while plenty good) aren't as weighty as Darwyn Cooke's Minutemen/Silk Spectre. Straczynski's Nite Owl (with art by Joe and Andy Kubert), however, truly distinguishes itself; in shining a light on a dark corner of Watchmen, Nite Owl accomplishes the best of what this Before Watchmen endeavor was capable of.

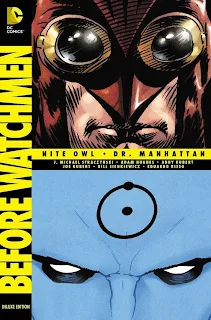

Review: Before Watchmen: Nite Owl/Dr. Manhattan deluxe hardcover (DC Comics)

Comments

To post a comment, you may need to temporarily allow "cross-site tracking" in your browser of choice.