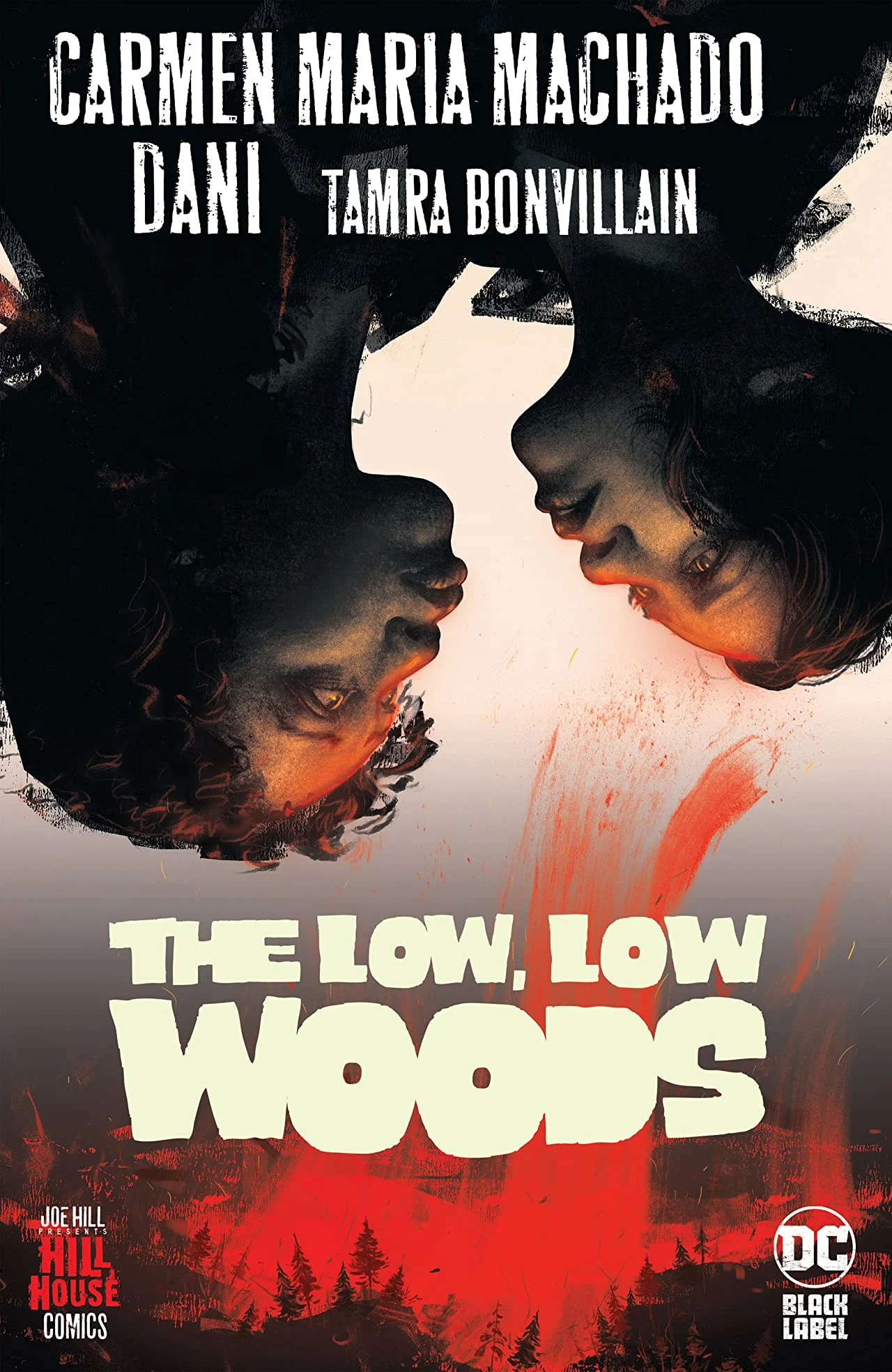

And so we come to the halfway point of the Hill House Comics imprint (an artificial distinction, perhaps, but the third of five books in publication order). The previous books in their own ways have challenged the horror genre, but Carmen Maria Machado and Dani’s The Low, Low Woods is something else. Monsters aplenty, though whether in the box office Woods would be deemed horror or instead fantasy/sci-fi is debatable.

It is not horrific (or horror-ific) in the sense of decapitated heads or lopped off hands. But indeed Woods is horrific, and disturbing, and to an extent the full horror of the book comes so late in the story that one cannot help be, if not horrified in the moment of realization, then horrified in the implications that come days afterward. Basketful of Heads and The Dollhouse Family have each in their own way a joyous kind of popcorn-flavored horror to them, a scary time to be remembered and revisited fondly. Woods also offers the joys of young adulthood and friendship, but in the end again it’s something else, an example of how the horror genre too can be an important reflection of the time in which we’re living.

[Review contains spoilers]

It bears pausing to admire what a rich world Machado creates in Low, Low Woods. There’s a little dissonance inherent in the beginning as one comes to understand that for this seemingly normal-looking Pennsylvania mining town, talk of witches or volcanic crevices in the middle of the park is not so weird, nor the appearance of skinless, shuffling zombies, despite no sense of being set other than in “reality.” Once the reader is inured to the twisted setting, however, it’s a perfect — or perfectly weird — place for a story of magical realism, where people transform as a matter of course, emotions share effortlessly across bodies, and mushrooms have varying effects in a subtle nod to Alice in Wonderland.

[See the latest DC trade solicitations.]

Woods begins in the certain genre of Stranger Things or Paper Girls — kids on bikes investigating weirdness in their town, trying to account for a lost block of time of the kind usually associated with possession or alien abduction. But what emerges is considerably more insidious, that essentially Shudder-to-Think, Pennsylvania, is a veritable rape camp where the men and boys have their way with the women and then drug them with the town’s magical water to make them forget. Early on, the mysterious happenings seem from the realm of X-Files — women waking up in strange places, weird creatures roaming the earth — but the eventual answers are all too commonplace: women wake in strange places because men leave them there, people lose time because they are drugged.

Though Machado hints as early as the second issue that sexual assault is taking place, it is not until the end of the fifth issue and into the sixth that the full horror is revealed — that what seemed supernatural has a terrible human explanation, and that the crimes committed in Shudder-to-Think are organized, even institutionalized. Machado and Dani do well echoing imagery, even color palette from the beginning of the book into the end, such to show the reader that what seemed fantastical was in fact much darker. In this way I think Woods does well sticking with the reader — days after reading, one realizes, “This was because of that, and this, and this …”

It helps greatly with the world-building, and Wood’s after-reading resonance, that Machado does not answer as many questions as she does answer. Protagonists and best friends El and Octavia share a psychic bond that neither questions nor that I saw adequately explained within the story. Related, perhaps, El’s mother was owed a debt by the town witch, but neither do we explicitly learn the nature of that bargain. And I can’t help but wonder about El’s father, who seems a nice man among terrible men, but who also seems somewhat ensorcelled, endlessly tinkering with miniature objects, and who is targeted by the town’s fierce deer-woman. Any of it could be related — the witch bonded El and Octavia, the witch made the father forget his own crimes, etc. — but near as I can tell Machado leaves it vague for the audience to wonder about.

Though concerned with sexual assault, all of the sex depicted onscreen in Woods is loving, surely an intentional choice by Machado in a book that could have been otherwise. It makes Woods not so much about the assault as about the trauma, the unbidden memories and the way in which trauma affects one in conscious and unconscious ways. In the era of #MeToo and increased discussion around sexual assault, Woods is defiantly ambivalent about how one should approach their trauma; rather than all of Shudder-to-Think remembering, Machado’s El and Octavia give them the choice to remember or forget, and one is not valued over the other. That Machado doesn’t reveal in the end whether Octavia remembers or forgets is the fine point on this; she’s a hero either way.

3.5

Rating

We’re well beyond coincidence here that The Low, Low Woods is Hill House’s third series with female protagonists (though the first written by a woman), and this one above all the others that not only challenges traditional conventions about women in horror, but that is very specifically a feminist horror story. I thought Basketful of Heads was Hill House’s gauntlet thrown, a pure depiction of its mission statement, but Carmen Maria Machado's Low, Low Woods overtakes that. With Basketful, Hill House was subversive and good; with Low, Low Woods, it’s important.

[Includes original covers, fantastic variants by Jenny Frisson, interviews and character sketches]

Comments

To post a comment, you may need to temporarily allow "cross-site tracking" in your browser of choice.