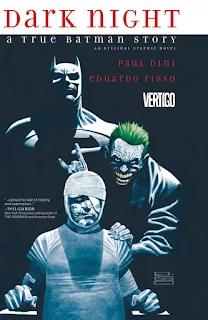

It seems overly cruel given the inciting incident of this book to say I didn't enjoy Paul Dini's Dark Night: A True Batman Story as much as I'd hoped, but that is the case.

The story of Dini's mugging, beating, and subsequent depression is certainly harrowing, horrific, and gripping, and what Dini presents feels true and eminently relatable. Artist Eduardo Risso does yeoman's work flitting between a variety of styles often on the same page to blend past and present and also reality and fantasy. But Dini's story is often over-narrated and lacks subtlety when it counts; "Somehow writing about Batman seems real pointless right about now," he states directly at one point. For a book that deals with the Batman: The Animated Series era, Risso's depictions of the comics characters are surprisingly off-model, and there's a couple artistic choices made that I just couldn't understand. Not to undercut this book's seriousness, but there's certain aspects akin to the theatrical Who Framed Roger Rabbit? that seemed to warrant an artist like Ty Templeton maybe in addition to Risso.

[Review contains spoilers]

That Dark Night is a story about Paul Dini's recovery from assault is something of a feint. Rather Dark Night is the story of Dini's isolated childhood and lonely early-adulthood as an introverted writer who found more acceptance in fantasy than people, which indirectly led to to his attack. In this, there's much that most comic book fans and teenage "nerds" will be able to relate to, and Dini explicates this landscape of public success and private melancholy with aplomb. Dini is poignantly honest about his own shallowness in his early professional days, and there's a beautiful arc in how he's matured some twenty-three years after these events.

Indeed the book's significant revelation is not Dini's attack, horrific as it was, but the depression that led him a year prior to "cut [him]self to ribbons" with his own Emmy award over being stood up by a date. Dini does not state it directly, but to the extent to which the aftermath of the attack helped him to set aside self-destructive tendencies and also a penchant for over-drinking, the assault in some respects helped Dini right his life. Equally as startling as the assault and the self-mutilation is a scene in which a young Dini almost accidentally shoots his own brother, made all the more shocking by the cartoony lens through which Risso depicts it.

But for the most part, Dini's story is very on-the-nose. No sooner has he returned to work after the attack than he tells his coworkers straightaway that he doesn't feel like writing Batman any more. I don't doubt the veracity of Dini's story but it seems a funny thing to just announce to one's Batman-writing colleagues; as well, here and when Dini mentions the same thing to his sister, the story seems to tell and not show this most important part (we never see him actually struggling to write, for instance, we only hear about it). Dini's writer's block essentially resolves itself after pneumonia ends his drinking and one chance encounter with an animation fan; though I agree the details of Dini's early life are important, the book is weighted much more toward the lead-in to the attack and the attack itself than Dini's ultimate recovery.

As I noted, Risso does well juggling a lot of styles; he also seemingly inks and colors, and it's effectively chilling when Risso transitions from a painterly approach to the more traditional, flat, Risso-trademark style just in time for the attack scene. But Risso's Joker here, for instance, looks like Mark Hamill playing the Joker, a semi-logical but not quite appropriate take for this story; his Two-Face, too, seemed egregiously different than the iconic Animated Series version. Risso has a great opportunity to draw Neil Gaiman's Sandman and Death in this book, but both are so completely unrecognizable that Death doesn't even have an ankh, an odd choice for a Vertigo book. I'm not sure why Risso draws Dini's psychiatrist with a provacatively-open blouse when there's no sexual tension between the characters. I also noticed Risso signs three pages within the story; I don't know if this is common for artists in graphic novels but it seemed an odd affectation.

Again, Paul Dini's Dark Night: A True Batman Story is a wise portrayal of the childhood and adulthood of fans of comics, cartoons, video games, or what have you, and how these "childish" pleasures continue into adulthood; it's also an honest confession on Dini's part. Certainly aspects of this book will stay with me for a long time. It did not come together for me as well as it was meant to, however, and my recollection of Steven Seagle's It's a Bird, the last time Vertigo published this kind of meta-DC examination, is that I found that book more effective than this outing.

Risso signs individual pages a lot. It's annoying and comes across as egotistical, to me.

ReplyDeleteI wonder if this was something DC agreed to publish after it had been originally conceived as an independent work, sort of like how Saving Mr. Banks was eventually released but not conceived by Disney (it features Walt Disney himself as a character, for the first time in film). This may account for the art discrepancies. Or they may simply have been creative choices.

ReplyDelete